Old Record bench planes show up on ebay on an almost daily basis and are frequently described by optimistic sellers as “Vintage”, but how old are they really?

To answer the question I have looked at the circumstances that prompted Record to start producing hand planes and in a subsequent post I will look at how the design has changed over time.

A thorough analysis on the history of Record can be found here. The site was created by David Lynch, an Irishman who spent the latter part of his life in Australia and who collected Record planes over a 40 year period.

Sadly Mr Lynch died in 2014, but a good Samaritan has taken on ownership of his website and continues to make it available to the public.

The early days

Although the Record trademark was registered in the early 1900s , the factory – established by Charles Hampton – did not start plane manufacturing until after the founder’s death in 1929 and first appeared in catalogues starting from 1931. As with so many other great manufacturers of the time the factory was based in Sheffield, England.

The range of hand planes produced by Record were copies of existing Stanley “bailey” pattern planes and Record’s inaugural manufacturing date coincides with the expiry of some of Stanley’s patents, as was true of other competitors to Stanley. From the turn of the century Stanley conveniently stamped the grant date of their most important patents into the bed of their planes:

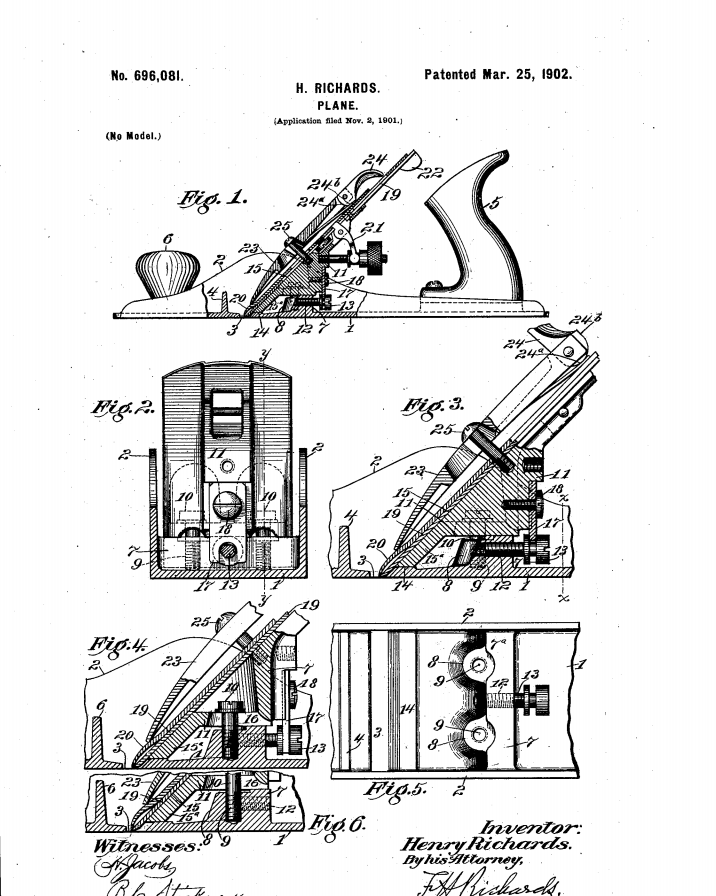

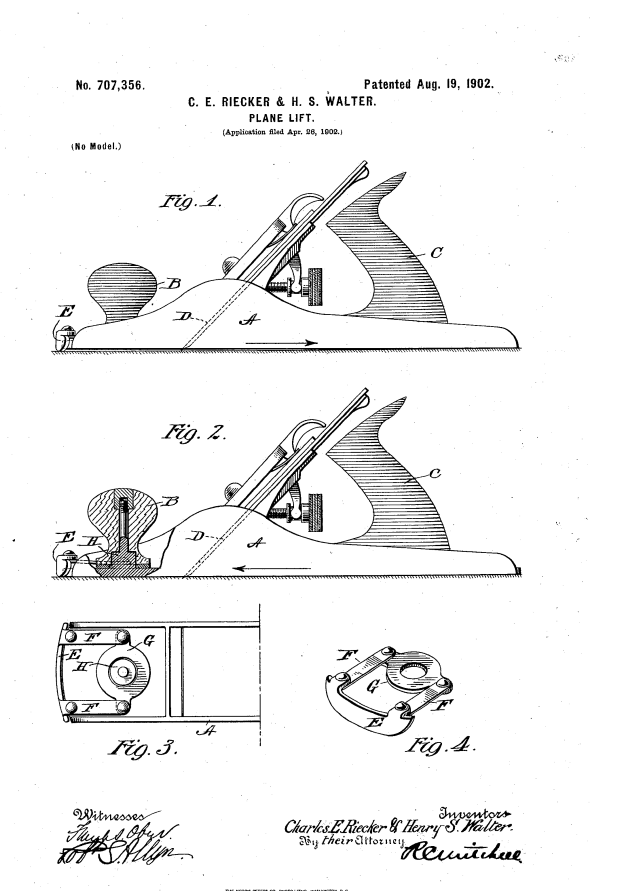

The patent dates are MAR-25-02, AUG-19-02 and APR-19-10. Patents grant the patent owner a temporary monopoly – typically 20 years for US patents. It is therefore to be expected that Stanley would have removed the patent references after the patents were no longer enforceable and his site confirms that the 1902 patent references were no longer stamped on plane base after 1923 and the 1910 patent reference disappeared in 1931.

Based on these dates alone it is plausible that Record waited for the final patent to expire before entering the market with a view to exporting to the US or because of fears that Stanley might be seeking protection in the UK.

Stanley & Chapman

Stanley started manufacturing in the UK in the late 1930s, having acquired J A Chapman Ltd (a maker of hand braces and the Acorn plane range based in Sheffield) in 1937.

Before then they apparently had a well-established import business in the UK, as indicated by the amount of advertising they were doing (you do not have to try hard to find adverts and catalogue entries for Stanley during the early 1930s) and the fact that so many USA made Stanley tools show up on ebay UK.

Until Stanley had their own factory in the UK the risk from local manufacturers must have been serious, since their exports were subject to a large import duty or arriving in the UK (in the inter-war years the UK underwent a period of protectionist economic policy in reaction to the concerns about the impact of high volumes of imports on domestic industries. This culminated in the 1932 general tariff tax of 10% on most imports). In addition they also had to cover the costs of shipping across the Atlantic. By 1930 Record must have been well aware of the opportunity both to copy their designs and to undercut them on price.

Having said that, in the Buck and Hickman catalogue from 1934 you can see that the Stanley and Record equivalent models were being sold at the same price, so apparently this tool seller at least thought Record could compete on its own merits; perhaps bolstered by the enthusiasm for the “Buy British” popular campaign of the 1930s.

the Bailey patents

It is hard to underestimate the success of the bailey plane design (and the fascinating inventor, Mr Bailey, warrants a separate post in the future) suffice to say that at the end of the 1880s pretty much everyone used wooden bench planes, and by the 1930s pretty much everyone had switched to using metal bodied planes which, although made my many manufacturers, all followed the same Bailey design pattern. To find out what how Stanley managed to hold off the competition until the 1930s I tracked down the main patents they filed at the start of the 20th century to protect their ideas.

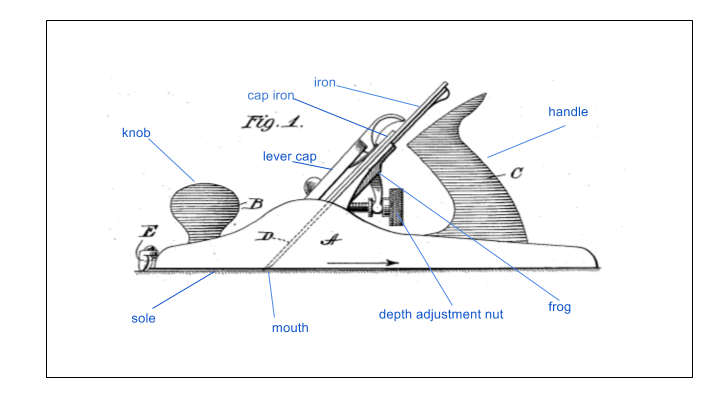

To understand the patents it is helpful to know a the names of the components of a plane.

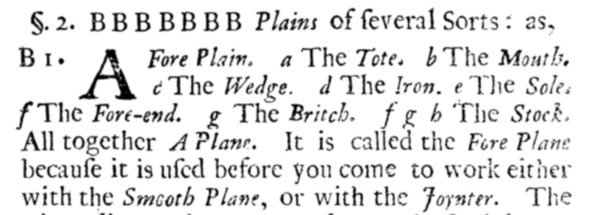

There are some regional variations on the terminology. For instance, the use of the term tote, rather than handle, is common in the US. I was surprised to find out that the American usage persists from an old English term that has fallen out of use here:

The term “cap iron” is the traditional usage and has persisted in the UK, but this part of the plane has been renamed chip breaker in the US. Finally, and perhaps more understandably the cutting iron is often referred to as the blade (both terms are used by Stanley in their patents).

The first patent US 696,081, March 25 1902 is for an improved frog mounting system where there are two bosses in the bottom casting to receive the frog – the surface of the bosses are ground flat to receives the rear of the frog and the leading edge of the frog sits on another flat surface immediately in front of the mouth of the plane. The previous design relied on a larger flat area that is machined in the bottom of the casting and this added weight and required more work to finish. You can see the design most clearly in fig 3 and fig 5 in the patent drawing page on the far left (shown below).

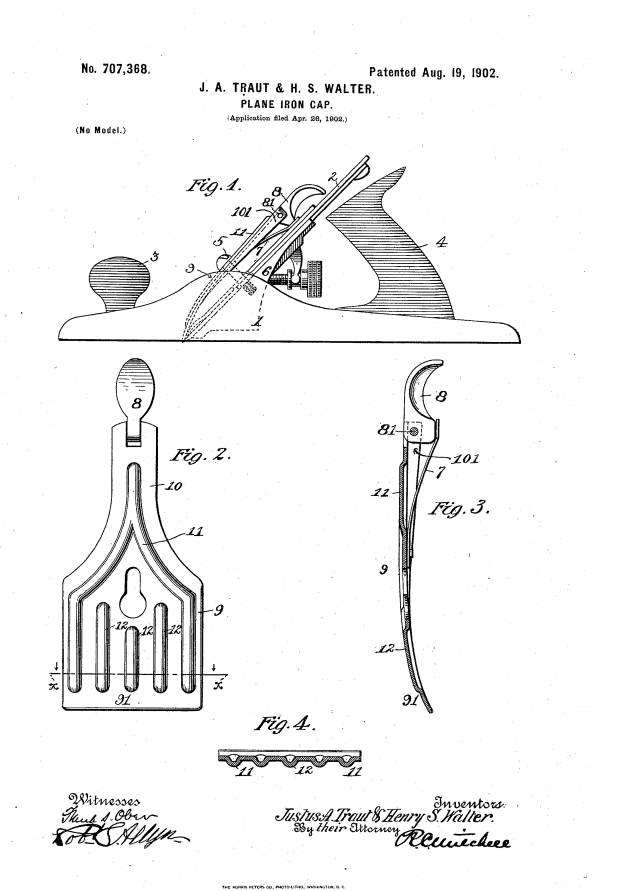

There are two patents for August 19 1902, the first is for a plane “lifting device” that was intended to help prevent wear on the blade by lifting the plane of the work-piece on the return stroke. As far as I can tell, this innovation never made it into production.

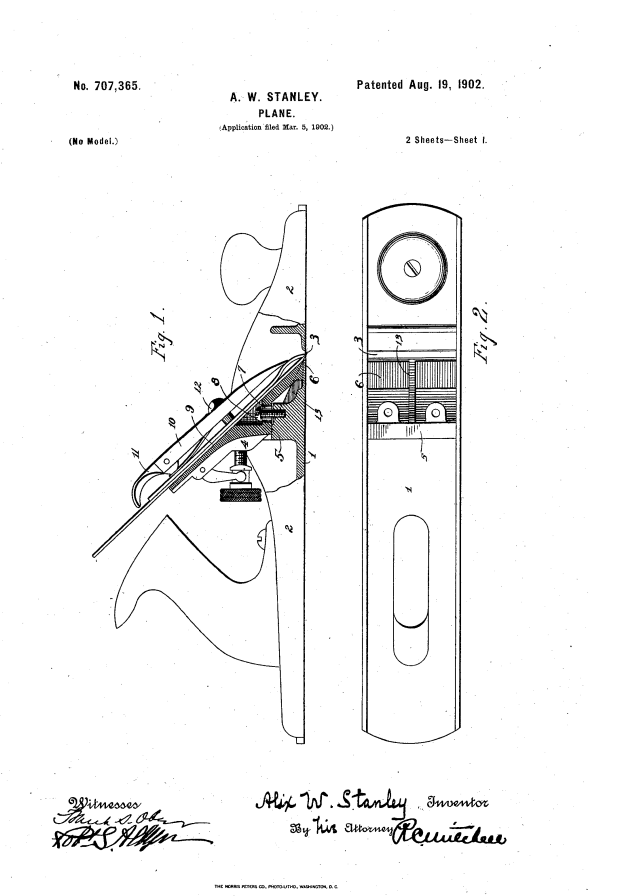

The second (US 707,365 August 19 1902) covers a rib cast into sole immediately behind the mouth that helps prevent the pressure from the lever cap deflecting the sole and also machining the rear of the mouth at an angle to better support the blade near the cutting edge. See the 3rd picture from the left for an illustration (below).

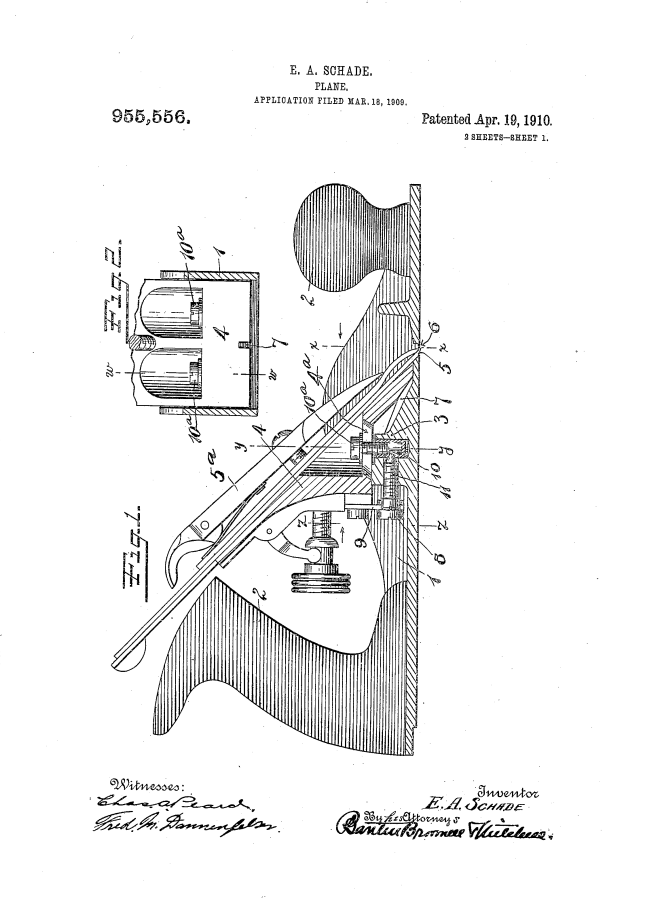

There are two patents granted on the 19 April 1910 are US 955,556 and US 955,557) . ‘557 describes a mechanism that allows the frog to be adjusted forward or backward (to close or open the mouth) by a set screw that is accessible below the frog’s depth adjustment nut. The idea is extended in ‘556 with the addition of two screws that allow the frog to be secured after adjustment – these are accessible from the rear of the plane and therefore allow the mouth to be adjusted without first removing the lever cap and blade/cap iron assembly.

In practice these last two inventions are of questionable benefit – you may never have the need to adjust the mouth size on your planes, and if you do, it is actually straightforward to tighten the frog mounting screws to a point where they both hold the frog firmly in place and allow adjustments to the frog position without removing the lever cap etc.

Nonetheless, the frog adjuster screw does at least allow the convenient positioning of the frog when assembling the plane and became the standard on metal bench planes and was duly copied by Record et al.

The more sophisticated mechanism that fixed the aforementioned non-existent problem with securing the frog after adjustment was used by Stanley on their premium ‘bedrock’ range of planes.

Once these patents had all expired in 1930 Record was free to copy Stanley’s designs and start up in competition, which is exactly what they did the following year. And the rest, as they say, is history.